It’s Purple Raining Sanctions: Litigation Regarding Prince’s Estate Provides Framework for Determining When Sanctions Apply Under FRCP Rule 37(e)

You may have read my colleague Starling Underwood’s post on two recent Second Circuit decisions discussing sanctions for spoliation. If you have not, I encourage you to read it here. The two cases Starling addressed, one involving the band Lynyrd Skynyrd and one involving Klipsch headphones, highlight multiple issues, such as the importance of a skilled e-discovery team, Electronically Stored Information (“ESI”) protocols and preservation, and the possible disproportionality of sanctions to case value. In this post, I follow up on that discussion by narrowing the focus to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure Rule 37(e), which is used to determine whether and what sanctions are appropriate when ESI spoliation occurs.

Now, you could listen to Skynyrd on your Klipsch headphones while reading about spoliation sanctions, but you could also listen to Prince sing about Purple Rain. So, to continue our music-themed sanction discussions and see Rule 37(e) be applied, I would like to turn your attention to a recent decision from the Minnesota District Court, involving the estate of the artist Prince Rodgers Nelson (“Prince”) and a sanctions motion for ESI spoliation. Paisley Park Enterprises, Inc. v. Boxill, No. 17-CV-1212 (WMW/TNL), 2019 WL 1036058 (D. Minn. Mar. 5, 2019). The court in Paisley Park provides a detailed review of the sanctions analysis under Rule 37(e), while dealing with a category of very common ESI data often at issue in litigation today – mobile phone text messages.

The Background of Paisley Park

The Plaintiffs in Paisley Park, Comerica Bank and Trust, N.A., acting as the representative of Prince’s estate (“Prince Estate”), filed suit against Boxill, Staley, Gabriel, Rogue Music Alliance, Sidebar Legal, PC and Brown & Rosen, LLC (“Defendants”) after multiple demand letters regarding the return of the music went unheeded by the Defendants. In response to certain deficiencies in Defendants’ discovery responses, the Prince Estate filed a Motion for Sanctions Due to Spoliation of Evidence. Id.

The court identified a number of facts that led to the motion and that would be relevant to its analysis of whether sanctions should be granted under Rule 37(e):

- Defendants were aware, or should have anticipated, ligation would occur months before the Prince Estate’s case was filed.

- Defendants utilized their personal cellular phones for business related communications, including text messages.

- The parties stipulated to ESI protocols that included taking reasonable steps to preserve relevant ESI data.

- There were multiple pretrial scheduling orders directing the parties to preserve responsive data, including text messages, and alerting them about penalties for failing to do so.

- The Prince Estate served broadly-drafted discovery requests that also indicated “document” should be defined and construed as broadly as possible under Rule 34.

- The Prince Estate sent a deficiency letter following Defendants’ discovery responses, particularly addressing the failure to produce any text messages from Defendants’ personal phones.

- The Prince Estate filed a Motion to Compel after receiving a third party production which included text messages with Defendants, resulting in an order for Defendants to produce relevant text messages.

- At a later meet-and-confer, Defendants reported they would not be able to produce any text messages as they had: (1) failed to disengage the phones’ auto-delete function; (2) failed to back up any responsive phone data; and instead had wiped and discarded multiple phones, even wiping and discarding one after litigation had begun. Id. at *1-3.

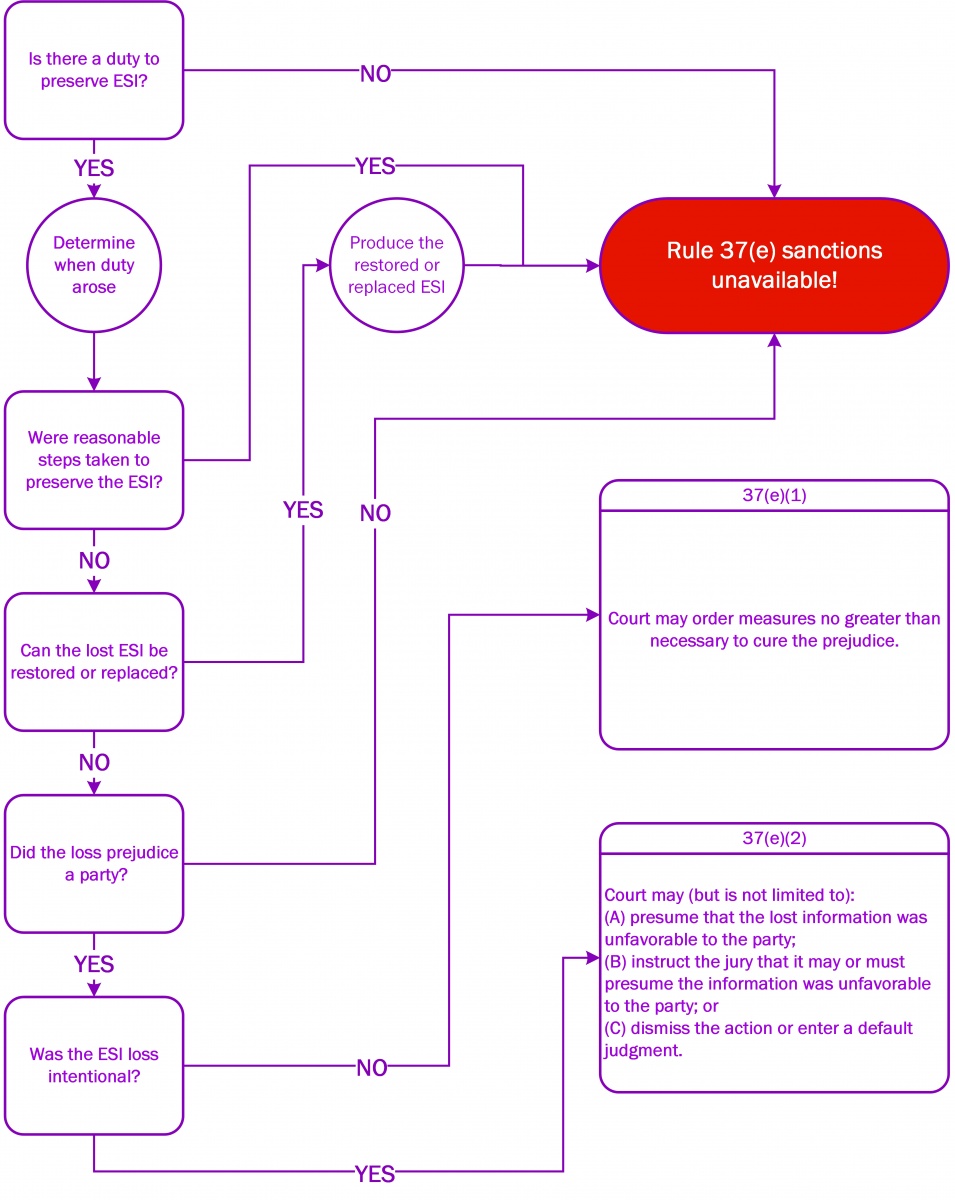

Because the Prince Estate’s motion involved the destruction of ESI, any sanctions determination would need to be in accordance with Rule 37(e), which provides the court with authority to sanction a party for the irrevocable loss of ESI data that the party has failed to take reasonable steps to preserve. Id. at *3.

Rule 37(e) Amendment and Sanctions Testing

In 2006, Rule 37(f) (now (e)) was created to address the growing presence of ESI data in discovery. This new “safe harbor” provision was intended as a restriction on sanctions and provided: “Absent exceptional circumstances, a court may not impose sanctions under these rules on a party for failing to provide electronically stored information lost as a result of the routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system.” Fed. R. Civ. P 37(e) advisory committee's note to 2006.

In 2015, Rule 37(e) was amended to address the exponential growth of ESI in discovery. This rampant growth, coupled with divergent federal circuit court standards created by the previous rule’s ambiguity, was causing litigants to bear increasingly burdensome ESI preservation costs due to the over-preservation of data out of fear of sanctions. Rule 37(e)’s intent is not to impose a burden of perfect preservation on a producing party. Rather, if “reasonable steps” are taken when preserving potentially relevant data, then that is sufficient to preclude sanctions under Rule 37(e). When determining what constitutes reasonable steps, a court should consider a multitude of factors, such as the proximate cause of loss, a party’s sophistication, and the proportionality of the preservation efforts. Fed. R. Civ. P 37(e) advisory committee's note to 2015 amendment. If you would like to read more about proportionality, my colleague Nicole Allen discusses proportionality and Rule 26 here as it pertains to discovery preservation and production scope.

If reasonable steps are not taken, then a determination must be made regarding whether the data loss causes prejudice to a party, if so, then measures “no greater than necessary” may be used under 37(e)(1) to cure the prejudice. However, if there was specific intent to deprive a party of the data, then more substantial sanctions are available to the court under 37(e)(2). It is important to note that, under both 37(e)(1) and 37(e)(2), the court is granted significant discretion in determining what sanctions would be appropriate. Id.

The current rule reads as follows:

FCRA Rule 37(e) Failure to Preserve Electronically Stored Information.

If electronically stored information that should have been preserved in the anticipation or conduct of litigation is lost because a party failed to take reasonable steps to preserve it, and it cannot be restored or replaced through additional discovery, the court:

(1) upon finding prejudice to another party from loss of the information, may order measures no greater than necessary to cure the prejudice; or

(2) only upon finding that the party acted with the intent to deprive another party of the information's use in the litigation may:

(A) presume that the lost information was unfavorable to the party;

(B) instruct the jury that it may or must presume the information was unfavorable to the party; or

(C) dismiss the action or enter a default judgment.

Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(e).

This new rule provided a more methodical approach to determining whether sanctions were appropriate under Rule 37(e), giving delineated remedies for spoliation only if specific findings were found. This revision did not create a new duty to preserve ESI, but was an incorporation of the common law duty to preserve data when litigation was imminent or anticipated. This change removed much of the ambiguity caused by the previous rule, which had often required a court to craft and justify remedies based on its inherent authority or variable state law. Fed. R. Civ. P 37(e) advisory committee's note to 2015 amendment.

Application of the Rule 37(e) Sanctions Test to Paisley Park

As applied in Paisley Park, the revised Rule 37(e) provides a clear test to determine when spoliation sanctions should apply. Using this test, the court in Paisley Park applied the fact pattern to each step in order to determine if sanctions should be levied against Defendants.

1. Was there a duty to preserve the ESI data?

In determining whether sanctions are appropriate, the first factor to consider is was there a duty to preserve the ESI data at issue, and if so, when did that duty arise. For example, a party may have had relevant or responsive ESI, but if it was purged prior to any anticipation or knowledge of litigation, then Rule 37(e) sanctions would be inappropriate even though the relevant data was irretrievably lost.

The Paisley Park court had little difficulty determining that a duty to preserve ESI data had been created and that it had attached months before the actual litigation was initiated. Defendants discussed releasing Prince’s music in emails that specifically mentioned the possibility of litigation, making the anticipation of litigation apparent. 2019 WL 1036058, at *3.

2. Were reasonable steps taken to preserve the data?

Next, the court turned to Defendants’ efforts to preserve ESI to determine whether they had taken reasonable preservation steps, as is required for those who would likely have relevant data, but noting there was no obligation “to keep every shred of paper, every e-mail or electronic document and every backup tape. Id. at *4 (citing In re Ethicon, Inc. Pelvic Repair Sys. Prod. Liab. Litig., 299 F.R.D. 502, 517-518 (S.D. W. Va. 2014)).

The court found that Defendants had not only failed to take reasonable steps to preserve the ESI, but also had affirmatively deleted responsive data from their phones. Weighing against Defendants was the fact that, despite anticipating litigation, Defendants failed to: (1) turn off the auto-erase function on their phones; (2) use a litigation hold to suspend any document destruction or retention policies as required by a “standard reasonableness framework”; (3) take simple, cost-effective steps to back up their phone data, especially given the importance of the issues and amount in controversy; or (4) retain their phones’ data, as required by the parties’ agreement, the rules of the court, notice from the Prince Estate and the court’s orders, but instead wiped and destroyed their phones. Id. at *4-5.

3. Can the data be recovered from another source?

If the data is retrievable from another source, such as a server or other custodian, then Rule 37(e) sanctions are not appropriate. Because Defendants’ internal messages were irretrievably lost, which Defendants did not dispute, and because other messages could only be recovered in a scattered and incomplete manner, the Paisley Park court found the messages to be not recoverable. Id. at *6.4.

4. What sanctions, if any, are appropriate?

If relevant data is irretrievably lost by a party under a duty to preserve it, the court must decide what sanctions are available. In addition to costs and fees, the Prince Estate sought monetary sanctions and jury instructions regarding Defendants’ duty to preserve and their failure to do so. Additionally, under 37(e)(2), the Prince Estate sought a presumption that the evidence was unfavorable to the Defendants, or alternatively, an adverse inference jury instruction. Id. at *7.

Under the tests of 37(e)(1) and 37(e)(2), a court may impose sanctions if it finds prejudice under (e)(1) or an intent to deprive under (e)(2). In Paisley Park, the court determined it would be appropriate to sanction Defendants under both subsections of 37(e).

First, under (e)(1), the court found the Prince Estate was unequivocally prejudiced because: (1) they had an incomplete record of the Defendants’ internal or third party communications; (2) the court and the Prince Estate would never know what was in the lost data or how important it was for the Prince Estate’s claims; and (3) the Prince Estate was “forced to go to already existing discovery and attempt to piece together what information might have been contained in those messages, thereby increasing their costs and expenses.” Id. Prejudice exists when relevant evidence cannot be presented by a party because of spoliation. Id. (citing Victor Stanley, Inc. v. Creative Pipe, Inc., 269 F.R.D. 497, 532 (D. Md. 2010)).

Second, under (e)(2), the court found that “Defendants acted with the intent to deprive Plaintiffs of the evidence.” Id. It can be difficult to prove intent with direct evidence, as there is rarely a “smoking gun” and there must be evidence of “a serious and specific sort of culpability” to show the intent to deprive. However, the court has significant leeway in what it can consider, such as “…circumstantial evidence, witness credibility, motives of the witnesses in a particular case, and other factors.” Id. The court had little difficulty finding the Defendants’ ESI loss was not just negligent, but intentional, as Defendants had: (1) failed to turn off their phones’ auto-erase function even though litigation was anticipated; (2) backed up other data on their phones in multiple ways; (3) wiped and destroyed their phones after litigation had commenced; and, most egregious of all, (4) wiped and destroyed a second device after the commencement of litigation and after receipt of discovery requests specifically targeting text messages and a pretrial order commanding ESI data be preserved. Id.

As a result of their egregious and intentional behavior, the court sanctioned Defendants under both subsections of 37(e), ordering them to pay “reasonable expenses, including attorney's fees and costs, that Plaintiffs incurred as a result of the … defendants’ misconduct” in addition to a court fine of $10,000. Id. at *8. Although the court felt the adverse inference or jury instructions that the Prince Estate had requested could be justified, it deferred that determination as the case and discovery were still on going and the record was not yet closed. Id.

Of particular interest is the Paisley Park court’s award of monetary sanctions under both 37(e) subsections, even though monetary sanctions are not listed in Rule 37 specifically. Courts are generally afforded broad discretion to determine what relief is appropriate and necessary to cure prejudice under 37(e)(1) and there is clear case law support for monetary sanctions under 37(e)(1). Id. Additionally, as EMA was subject to 37(e)(2) sanctions, the court is able to order “any remedy that fits the wrong,” including monetary sanctions, as the list of three sanctions in the rule is not an exhaustive list of remedies available to the court. Id.

In addition to providing a helpful framework for a Rule 37 sanctions analysis, Paisley Park is a cautionary tale to those who do not take seriously the duty to preserve ESI data - even text messages on a personal phone.

DISCLAIMER: The information contained in this blog is not intended as legal advice or as an opinion on specific facts. For more information about these issues, please contact the author(s) of this blog or your existing LitSmart contact. The invitation to contact the author is not to be construed as a solicitation for legal work. Any new attorney/client relationship will be confirmed in writing.